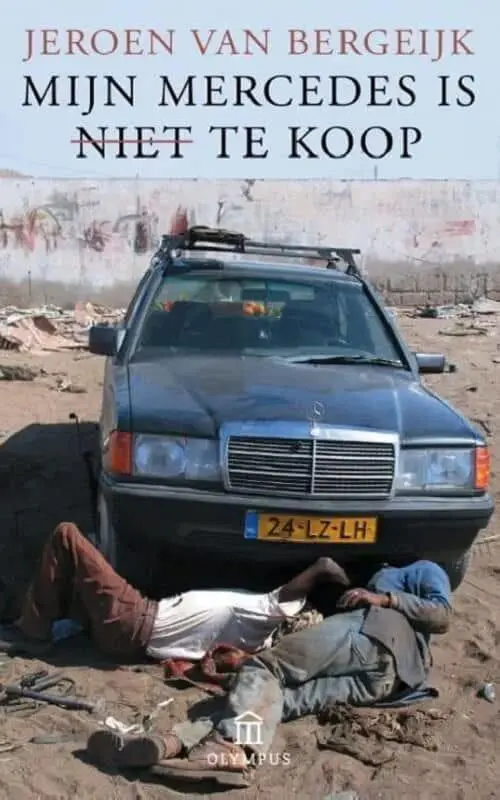

A battered Mercedes in Burkina Faso

It all started when Van Bergeijk attended a wedding in Burkina Faso and spotted a battered Mercedes driving around, complete with a PSV sticker on the dashboard and an NL sticker on the boot. How on earth had this car ended up here? A year later, he set out to investigate—both to sell an old Mercedes for a profit in an as-yet-undetermined African country and to find like-minded adventurers who drive rickety cars to Africa.

"Turkenbak"

The car Van Bergeijk uses to cross Africa is a Mercedes 190 D, known in the Netherlands—somewhat unflatteringly—as a

Turkenbak. Built in 1988, it has 220,000 kilometres on the clock. Its previous owner was a police officer who had bought it in Kosovo from a rebel fighter. As the book follows the car's journey in search of a new African owner, the reader also gradually uncovers more about its past owners.

Old diesel to Africa

Chugging along, the old diesel makes its way through Germany, France, Spain, Morocco, Western Sahara, Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Mali, Ghana, Togo, and Benin. You might think a car like this wouldn't be in demand in Africa, but Van Bergeijk quickly learns the opposite is true—hence the book's title. Time and again, he has to explain that his car is

not for sale, even though he could fetch a decent price for it as early as North Africa. In Mauritania, he observes, nearly half the population seems to drive a 190 D. But no, his Mercedes is (still) not for sale—the adventure can't be cut short too soon. After all, there’s still a book to be written.

Tipping and bribing

You could call it raw investigative journalism—personally retracing the route that the battered PSV-stickered Mercedes in Ouagadougou must have once taken. Crossing the desert, Van Bergeijk gets hopelessly stuck, forced to choose between either speeding over the washboard-like sand roads or creeping along painfully slowly. Between all the tipping and bribing (

"tjep-tjep") he also faces serious car trouble. After countless dry-witted and entertaining anecdotes, you come away with a much clearer picture of what it’s like to drive an old Mercedes across Africa. The book isn’t necessarily a must-read for those looking for detailed insights into the destinations along Van Bergeijk’s route—that’s not its purpose.

Putting things into perspective

Despite being scammed multiple times and having to bribe people almost everywhere, Van Bergeijk ultimately remains optimistic about Africa. Anyone who has travelled the continent will recognise what he means when he says Westerners tend to focus only on things that don’t really matter. So, if you’re looking for an Africa travel book that helps you put things into perspective, look no further.

Two excerpts from My Mercedes is (not) for sale

Prologue

I don’t think I would have ever come up with the idea myself. To visit Ouagadougou, I mean. A good friend was getting married there, in the capital of the West African country Burkina Faso. To a Burkinabé. And I didn’t want to miss it. The wedding celebration lasted three days. On the final evening, exhausted, I climbed into a taxi. Now, Burkina Faso is one of the poorest countries in the world, so I knew most cars there weren’t exactly the latest models. But this one was something else entirely. The car was dented on all sides, its headlights were missing, and its tyres were completely bald. Thick, black smoke billowed from the exhaust pipe. The interior wasn’t much better: where the speedometer had once been, there was now a gaping hole. The springs poked through the seats. The door panels were largely missing, exposing bare metal.

On the cracked dashboard was a PSV sticker.

A PSV fan in Ouagadougou? I tapped the red-and-white logo of the Eindhoven football club and asked the driver if he was a fan of Dutch football.

He didn’t understand what I meant. He had never heard of PSV, nor did he care about football in the slightest. He didn’t even know where the Netherlands was. That sticker had always been there. And it looked the part—yellowed, frayed at the edges, as if someone had tried unsuccessfully to peel it off. How did that sticker end up in an African taxi? Perhaps the previous owner had been a PSV supporter? As intriguing as that thought was, a PSV fan in Burkina Faso seemed unlikely. Wasn’t it more plausible that an even earlier owner had been the fan? That must be it: the car had come from Brabant. And sure enough, as I stepped out, my suspicion was confirmed.

On the back of the car was a white

NL sticker.

That taxi in Ouagadougou was a Mercedes 190 Diesel.

The purchase

Advertisements like this appear weekly on the Dutch website Marktplaats.nl:

"For sale: Mercedes 190 D

Price: €1,400

Mercedes 190 D, year of manufacture 1988, mileage 220,000 km, alarm, anthracite colour, 4-door. The car is in excellent condition, has just had a minor service and a valid MOT."

This one catches my attention because everything seems right—the type of Mercedes I’m looking for, a reasonable asking price, not too many kilometres on the clock, and a recent inspection.

"The phone hasn’t stopped ringing," the seller tells me when I call him on a Saturday morning.

"You can come and see it, but whoever says yes first gets it."

I rush to Buitenplaats Ypenburg, a newly built residential area on the outskirts of The Hague. The Mercedes’ owner is called Ronald. He works for the police. Which, in his view, means he can be trusted. Ronald is a muscular man with a short haircut—exactly how you’d picture a police officer. He’s brief, a bit strict, but not unfriendly.

We walk over to his Mercedes, which stands out among the gleaming, brand-new mid-range cars parked in Ronald’s neat street. The paintwork is dull. There’s a crack in the bumper. The sunroof won’t open. The driver’s seat is sagging, and the central locking doesn’t work.

Ouagadougou

That taxi in Ouagadougou hadn’t left my mind. On the flight home, I’d been wondering how that car had ended up there. I imagined a Dutch development worker who had inherited the Mercedes from his uncle and shipped it via the neighbouring port of Benin. Or maybe an African immigrant who had bought the car from a contractor in Eindhoven and sent it to his family in Burkina Faso. Or a Dutch adventurer who had driven that Mercedes 190 straight across the Sahara to sell it to the highest bidder in Ouagadougou. But what was the real story? How did a Dutch car end up in Africa?

A seventeen-year-old car

Take Ronald’s Mercedes. A seventeen-year-old car is essentially living on borrowed time; in the Netherlands, cars have an average lifespan of just fifteen years. For a car like Ronald’s, there are really only two possible futures. The most likely scenario is the scrapyard—not because the car is in terrible condition, but because any future repairs will soon exceed its market value. In the Netherlands, Ronald’s car is no longer useful. But in countries where repair costs are much lower, it still has value.

That brings us to the second scenario: export. Of the more than seven million cars on Dutch roads in 2005, a quarter of a million were exported by the end of the year. All wealthy Western European countries export their old cars—millions in total. Most now go to Eastern Europe, but a significant minority—an estimated 500,000 per year—ends up in Africa. That PSV-Mercedes in Ouagadougou is not alone. A salesman’s Opel Astra from Almere is now a bush taxi in Accra. The Toyota Corolla of a housewife from Zoetermeer is being driven by a camel trader in Mauritania.

Destination: Africa

Most cars bound for Africa leave the Netherlands by sea, but a small number are driven there. In fact, driving a second-hand car to West Africa has been a favourite pastime of adventurous French, Belgian, German, and Dutch travellers since the 1970s. These travellers are like our migratory birds—black-tailed godwits, terns, and swallows. Every winter, they head to West Africa to sell their old bangers for a tidy profit in countries like Mauritania, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Along the way, they must bribe customs officers, befriend corrupt police, but above all, they must cross the Sahara.

Test drive

I take Ronald’s Mercedes for a test drive. Mechanically, it seems sound—the engine runs smoothly, the brakes are fine, it’s a bit sluggish on acceleration, but the gearbox feels good. It may look a little scruffy in this suburban neighbourhood, but for a seventeen-year-old car, it’s in decent shape. The taxi drivers of Ouagadougou will stare at me with envy. I manage to get Ronald to knock €200 off the price, and moments later, it’s mine—an African taxi in the making.

Copyright: Uitgeverij Augustus & Jeroen van Bergeijk

More about the book:

My Mercedes Is (Not) for Sale

Publisher: Uitgeverij Augustus

ISBN: 9045700379

Pages: 222

Retail Price: €12.50

More about Jeroen van Bergeijk

Jeroen van Bergeijk (born 1965) is a journalist, writer, and amateur car dealer. His work has appeared in publications such as NRC Handelsblad and HP/De Tijd, as well as internationally in

The New York Times, Wired, and

Rolling Stone. In 2002, he published

U.S.1 – America after 9/11, a book exploring post-9/11 America six months after the attacks.

In April 2006,

My Mercedes Is (Not) for Sale was released, detailing his journey across the Sahara in an old Mercedes, attempting to sell it for a profit in Burkina Faso. The book was reprinted five times within a short period.

In 2007, he co-authored

More than the Facts with Han Ceelen, in which they interviewed thirteen leading Dutch-language non-fiction writers about their craft.

In June 2009,

Toubab! Dutch and Flemish Writers on Africa was published, an anthology compiled by Van Bergeijk.

For more information about Jeroen van Bergeijk, visit his website:

www.vanbergeijk.com

or

www.mijnmercedes.nl, a website created specifically for the book.

All images in this article were taken by Jeroen van Bergeijk.